The Right/Wrong Game

In relationships

In relationships

Beyond our ideas of right-doing and wrong-doing,

there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

— Rumi

You’ll see this quote by Rumi on a lot of couples therapy websites. It’s a good quote, and we all have some idea of what it means. Most of us have had the experience of getting caught up in the unhelpful “who’s right” type of argument. It’s a power struggle. For some couples it’s a chronic, toxic pattern.

The need to be right can be addictive, and it can also destroy relationships.

Here’s an in-depth look at why right and wrong is usually a lose-lose contest in relationships, the illusion of “being right,” and how to get out of the trap.

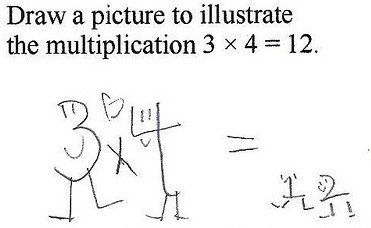

Let’s examine the ideas of “right” and “wrong.” We apply these evaluations to everything from math problems in school to how the house should be cleaned to how we should feel about each other, on up to how kids should be parented, or a nation ruled. But there’s a huge range of complexity and applicability from one end to the other.

In the strictest sense, right and wrong describes a degree of correspondence between two or more things. For example, elementary math problems can be judged correct or incorrect based on whether they adhere to the rules of the specified mathematical system. (Note, however, that even at their “simplest” they are based on lots of presuppositions, definitions, etc., such as what base is being used, what the symbols mean, how the symbols relate to each other, etc.) Similarly, Newtonian physics, common engineering and basic machines are fairly easily described in terms of right and wrong operations, principles and rules of behavior (physical “laws”).

Human Scale and Perception

But physics becomes much less determinate as it moves into the quantum realm. Observations and behavior become more probabilistic instead of absolute. I believe this has to do with the scale of human perception. Mechanical properties that we perceive with our bodies directly are easier to formulate rules about. As we stretch the boundaries of our perception through instruments, the rules become blurrier, and harder to describe in human terms.

And even our direct physical perception is quite limited. Of the electromagnetic spectrum, we only perceive a tiny fraction. We can’t detect infrared light, our hearing is bounded to only a subset of possible frequencies, and we are all constantly swamped in a wash of TV, radio (including cellphone), and satellite waves to which we are completely oblivious without the proper decoding instruments (which translate all those things back to human scale).

Our minds constantly “knit over” irregularities of perception, most of which never enter our awareness.

Yet even human scale perception — much less human communication — is enormously complex, biased, and lossy. Google some optical illusions and see how crazy vision can be (see the crawling lemons below). Look up the experiment for experiencing your blind spot and you’ll see that there are substantial holes in our vision. Many people go their entire lives without experiencing these literal visual gaps, though they’re always there, even as you read this page. As Julian Jaynes pointed out in his brilliant book “The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind,” our minds constantly “knit over” irregularities of perception, most of which never enter our awareness. Similar illusions can be demonstrated in every sensory modality (here’s a great audio demo: McGurk).

Wright-or-Wrong Koans

Is it right or wrong that:

the sun burns

water is wet

we breathe

we get angry

we get sad

we jump up and down

As you can see, the question doesn’t really apply. Right and wrong are based on some kind of comparison, or context. That the sun burns, or we get sad, are just how things are; they are statements of what is. Evaluation enters the picture only with context, and mostly in terms of consequences. If the sun makes us warm on a hot day that can be uncomfortable. If it makes us warm on a cool day that can feel good. If we jump up and down at a rock concert that’s expected. But at a classical concert in a symphony hall the same behavior could get us thrown out! Some would say that jumping up and down at the classical concert is wrong, but that’s only in relation to social norms and expectations, which is determined by the web of culture (e.g., in the United States, in a typical symphony concert hall, with the particular rules and mores of that hall).

Standards

Ultimately, right or wrong are judged in reference to some standard. At the easy (and more applicable) end of the spectrum are things like math, engineering, and use of products, where there are clear rules or instructions for usage and behavior. These are some of the common environments that condition and reinforce the idea that there can be such a thing as indisputable right and wrong. Originally the idea of right and wrong probably starts for each of us with injunctions from our parents: do it this way, don’t do it that way. It’s relatively easy to demonstrate that there are right and wrong ways to drive a screw, add some numbers together, or bake a cake.

But beyond those kinds of rule or instruction-based domains we get into values and the plot thickens considerably. Consider cooking a steak. Some will like it rare, some well done. Some people like sauces, some like it plain. You can argue right or wrong, but really how a steak is done is about each person’s preference, or individual values.

Legal/judicial systems have rules for how society operates, and these systems make decisions about right and wrong, but even within such a system different lawyers and judges have different opinions about what’s right and wrong.

A legal system, for example, attempts to create standards, but there are fringes and huge grey areas where there is no clear answer and decisions are made based more on belief systems than any absolute. Furthermore, the legal system of one culture might be quite different from another culture. Is one right and one wrong, or are they just different systems? Of course, as with partners in a relationship, each culture will argue theirs is the right way! Legal systems and governments depend heavily on values (such as those outlined in the Declaration of Independence: We hold these rights…). Values, in turn, are emotionally charged beliefs. So ultimately, I maintain, human behavior and experience are always rooted in emotions.

Feelings and Relationships

It has been said, you can insist on being right and you can be alone. Through his rigorous and extensive couples research, John Gottman points to contempt as the most significant single predictor of relationship failure. Contempt is all about right and wrong.

Insisting on right and wrong is antithetical to inter-dependent, co-equal, cooperative relationships because it doesn’t acknowledge legitimate differences in values and emotional responses.

In hierarchical systems, such as business and military organizations, right and wrong has a place as a means of establishing and maintaining consistency, efficiency and authority. However, in our culture intimate relationships are presupposed to be fundamentally equal and interdependent, with neither partner being overall “better than” than or “superior to” the other.

When establishing right and wrong takes precedence in a relationship, it creates a winner and a loser: one-up and one-down. The one-up person gets to feel good and big, while the one-down person feels bad and small. Sometimes partners switch off on these roles in different areas. Over time these interactions usually lead to both partners placing a premium on asserting their “rightness” in order to feel good. The charge you get when you feel right can be addictive. The unfortunate side effect though, is that often both partners over time end up feeling “wrong” and bad in each other’s eyes.

Differences become contests of right and wrong, and the essential feelings of safety and comfort that we seek in relationship get replaced with feelings of helplessness, mistrust, inadequacy and pain.

It’s All In Your Head

Right and wrong are about categories, absolutes, linear causality, and comparison to an “objective” (meaning definable, or agreed upon) standard. But nature and relationships are about relative values: better and worse, multiple perspectives, circular causality, and fluidity. Right and wrong — and categorical thinking — are aspects of our mind that we project into the world to make sense of it. As the philosopher Immanuel Kant pointed out, when you see three trees on a grassy hill, the number three is not out in the trees. The number three is in our minds. By the same token, red, green, soft, cold, high pitched sounds, low pitched sounds, messy, neat — these are all ways that we divide up the infinity of the universe to try to make sense of it. Same thing with right and wrong.

We do not see the world as it is, we see the world as we are.

— Anais Nin

Right/wrong thinking can be useful for some things, but it is inherently anti-relationship, especially the more urgently it is pursued. Couples commonly get so caught up in trying to reconstruct a past argument through asserting the “rightness” or “facts” of their different points of view, that the original argument gets lost in the heat of the battle for “accurate” reconstruction.

However, accurate reconstruction is often impossible exactly because we each perceive things so differently for a host of perceptual and psychological reasons unique to each individual (not to mention well-documented memory inaccuracies which most people underestimate). Of course a large part of the battle for accurate reconstruction is each partner pleading to be represented the way they would like to be, or trying to correct misunderstandings.

Adding to the confusion, language is often more imprecise than we might imagine or wish. In poetry ambiguity can be charming, but in personal relationships the same ambiguity can lead to all kinds of problems. Consider the phrase “Time flies like an arrow.” As George Lakoff explains in his fascinating book “Metaphors We Live By,” this seemingly simple phrase can be taken at least four entirely different ways. One way most people wouldn’t think of is a fanciful idea that there are insects called “time flies” that have affection for an arrow! I’ll leave the other interpretations as a challenge to the reader.

So sadly, the struggle to define the “reality” of the situation ends up eclipsing any intents to correct confusion or set the matter straight.

The antidote is to drop the fight for who’s right. Let go of that urge to say one more thing to persuade your partner. Take a few deep breaths. It isn’t working and it’s not worth it. Instead, focus on working towards these understandings:

How we differ as human beings

What is meaningful and important to each of us

What my impact is on my partner and how I can improve that

And how we can connect with, and comfort each other through a deep understanding of our individual differences.

Am I right?

(I’m a psychologist with a private practice in Noe Valley, San Francisco. Now serving all of California via telehealth.)

[Image credits: Butting Heads — The Stocks, Math Problem — The Stocks, Lemons — see link in article, Gavel & Scales — PRSA-NY, Three Trees — The Stocks]